A story appeared in the New York Times on Sunday about our hometown - Tamaqua PA. A lady who came to Tamaqua to teach a course at the local community college - wrote this story that of course has the "natives" restless.

Tamaqua was a booming town - when coal was king - but today there is very little work in the town - and most of the kids must move away to get work. When the mines closed down - my Dad had to commute to Philadelphia - 90 miles each way - to find work. He did that for 15 years while I was growing up. One time he put a deposit down on a "fancy" house in Fairless Hills/Levittown - but my Mom threw a hissy fit and refused to leave the "valley."

I spent most of my life in Tamaqua - 55 years - and taught in the local schools for 33 of those years. When Nancy was recruited to be a professor at Florida State University - I could no longer justify staying in "the bubble."

As much as I can see "both sides" of the Tamaqua story - I am proud to say I spent most of my life there - and I love the people and the place dearly.

Here is the New York Times story -

Coal Miner's Granddaughter

By BATHSHEBA MONK

Over lunch one day, I tell a friend that I'm taking a teaching job at a community college in Tamaqua, Pa., not far from where I was born. After a lifetime of staying away, I moved back to the state two and a half years ago and now live in Allentown, but I haven't been back to the coal region since I was 18.

My friend, an antiques dealer who goes picking in the area, says he drove through there last Tuesday. "It looks like there was a nuclear accident in Tamaqua and the survivors stayed on," he says, and laughs. I pretend to laugh with him, but it feels as if he's making fun of my mother. I can do that. He can't.

Although Tamaqua is only an hour northwest of Allentown, it might as well be in another country in another time. On the first day of school, as I drive up Route 309 over Blue Mountain, the car engine strains to make the steep grade, then my cellphone cuts out. On the edge of town, I see a worn sign that says "Coal for Sale" that must be 30 years old. Abandoned strip mines surround and define both the town and the people, who look flinty, dust-covered, squinteyed.

At a stoplight, I stare at a fat boy delivering fliers to houses from a canvas pushcart. He turns to give me an angry look, then suddenly darts his cart into the street toward me. I lock my car door and plead with the light to change. He reaches the car and rams my door as the light turns green. I shift gears, turn left and gun it up an almost-90-degree hill, zoom over the tracks in front of a slow-moving freight train, past row houses that have been clinging to the hill for a hundred years, crest over a street that is so steep it actually seems to be tilting backward and finally pull right up into the parking lot of Lehigh Carbon Community College.

The class I am teaching is Technical Reporting. That's what the nice dean told me. "So much real-life experience!" he had exulted over the phone. "Just what these kids need. And being from here, you can relate to them."

I have 10 students, who are already seated when I enter the classroom. Eight are boys, who slouch low. Baseball hats stitched with contractors' names are pulled down over their eyes. One wears a sleeveless T-shirt and rotates his right arm in front of him, admiring his triceps. The two women are housewives. One has embroidered teddy bears on her turtleneck sweater.

They are here because John Morgan, who basically invented thermal underwear and made his fortune here, bequeathed part of that fortune to build this campus so that any student who graduated from Tamaqua High could have two years of free college and wouldn't have to leave town. Which is a hell of a booby prize, I think, because my view is that there is no reason to stay. My agenda in agreeing to teach this class isn't to give these students skills to help them thrive in Tamaqua. It's the opposite: to inspire them to leave. I carry totems in my briefcase — bus schedules to Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and beyond. Is there anyone more obnoxious than a missionary?

To get to know them, I ask each student to tell me what he or she wants to be: construction manager, heavy-equipment operator, logistics specialist. "Cop," one housewife says. "Why not D.A.?" I press. She doesn't answer. I tell the boys that unless they are bald or have a scalp disease, I would like them to please remove their hats, which none do. So I move on to my "real-life experience": Army in Germany, real-estate manager for a big insurance company in Boston, small-business owner in Allentown. I have lived all over the world, I say. And listen! I, myself, grew up in a coal patch near here. I name the patch. The hats are pulled even lower.

The fact is that I come from a long line of people who pick up and leave when things stop working out. My grandfather migrated from Poland to Hazelton, Pa., to mine coal, and when the mines closed, my father hitchhiked two hours south to Bethlehem to roll steel, and when the furnaces shut down, my brother moved to Nigeria, where he drills for oil. It seems natural, American really, to move on. Aren't most of us descended from people who did just that?

I ask the class to write what they hope to learn from me on index cards I give out, and they hand the cards to me as they file out. How to write a bid proposal. How to create a technical manual. No one, it seems, wants to learn how to escape.

At the bottom of one card a student has written: "Who do you think you are?"

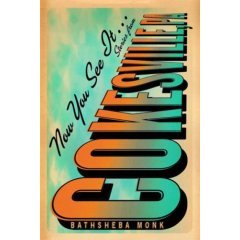

Bathsheba Monk is the author of a collection of short fiction, "Now You See It. . .Stories From Cokesville, Pa.," to be published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in June.

No comments:

Post a Comment